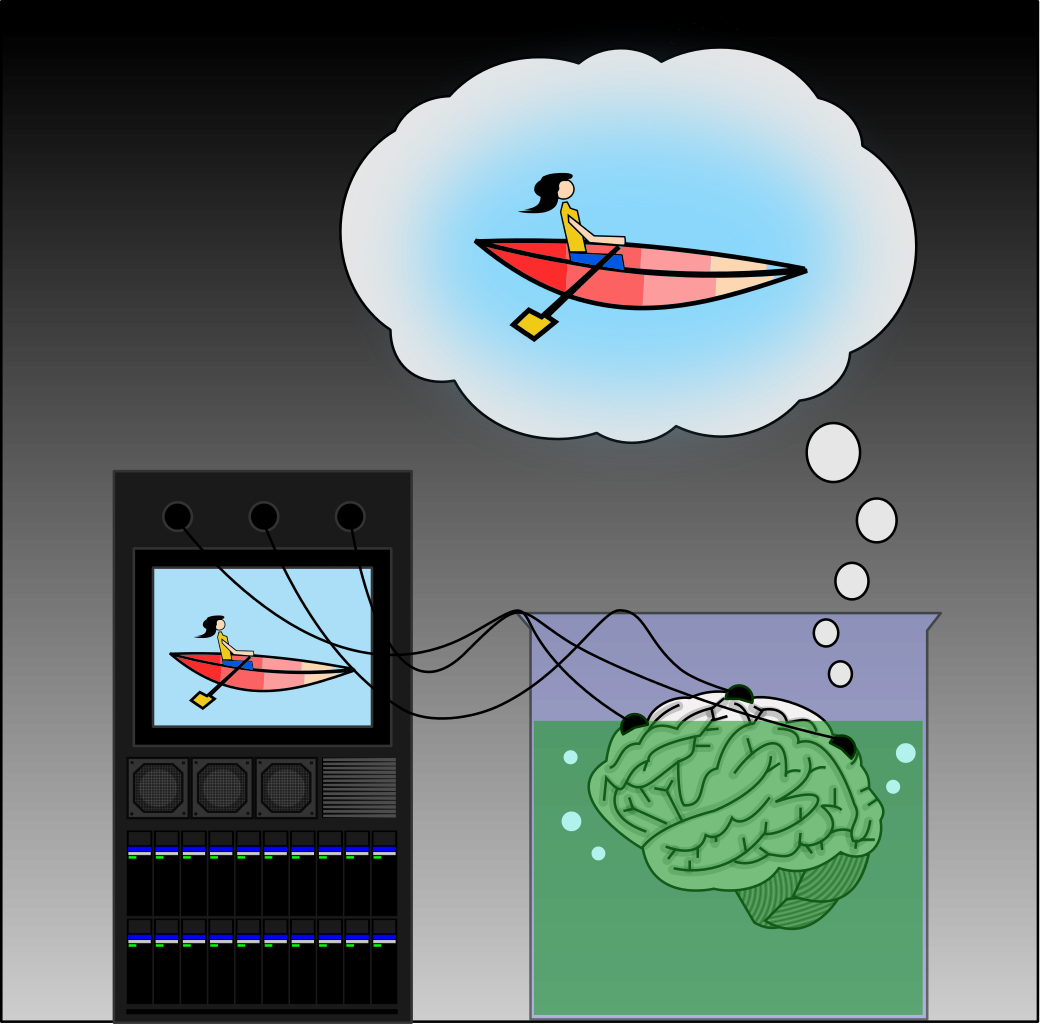

One of the reasons that I became a teacher is that I love the life of the mind. I’m at my happiest with big stretches of time to sit and think and read and write and talk. I would be just fine as a brain-in-a-vat.

And yet – over the past three years, I have used my body to bring two other bodies into this plane of existence, a brace of small people who do not currently lead the contemplative style of life that is my own preference, but rather experience and interact with the world on the most concrete terms. Instead of sitting quietly with some books and a cup of tea, I now spend my days wrestling them into their adorable miniature clothing and snatching choking hazards out of their sticky, chubby hands.

It was a revelation to me to learn (from the 1000 Hours Outside podcast) that my small humans’ flailing about in three-dimensional space is actually essential to the growth of their minds: that the challenge and stimulation of running on uneven terrain or climbing up a rock wall is what is forging strong neural connections in their brains that will one day help them to follow to logical progression of an argument or perceive similarities across different subjects.

This should have been more obvious to me. A year of virtual instruction taught us that the loss of physical presence made it difficult for students to learn.

So I was intentional in my curiosity this year about the relationships between students’ bodies and minds. Here were some of my attempts as sussing that out within the discipline of English:

We did a lot of art as a form of assessment. We made posters about the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals in The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind, we illustrated diagrams of the Hero’s Journey in our summer reading books, we made maps of the locations in the Odyssey, we hand-lettered quotations from Romeo and Juliet, and we drew portraits from The Count of Monte Cristo. We did all of this on paper, with pens and pencils and paint. Students had to put away their phones and laptops. Students, for this brief period, did not want to look at their phones and laptops.

We represented reality using models. A grant from Donors Choose funded windmill kits for students to understand – and then write about – how renewable energy works. We made miniature paper Globe theaters, and we considered how buildings can function as texts with the architects as authors and the inhabitants as readers. We reflected on how the spaces we occupy – the configuration of our desks, the patterns of lights, the acoustics – stimulate different kinds of responses in our bodies and our minds.

We played with poetry. A couple of thoughts from Thomas C. Foster in How to Read Poetry Like a Professor have been rattling around in my head for months as I worked through this:

“Reading poetry requires more than just your brain. Writing poetry is a full-contact activity; so, too, must we bring our entire being to bear on the act of reading it.” (7)

“Poet Robert Pinsky, in The Sounds of Poetry, says that poetry is a ‘vocal, which is to say bodily, art.’ That is, he explains, that it is meant to be spoken and heard, which involves breath and vocal cords and diaphragms as eardrums, among other bits and pieces of a person [....] We have bodily as well as emotional or intellectual responses to poetry.” (13)

We learned about meter by walking to the beat. I made students shuffle up and down the fire lane of the school pretending to be pirates (repeating “I am a pirate with a wooden leg” as a perfect example of a line of iambic pentameter). Then I made them gather silently and put their fingers to their pulses in their necks. “What do you feel?” I asked, channeling Robin Williams from Dead Poets Society. “Embarrassment,” one of my students said. And while I acknowledge that clever quip, I think that students also experienced that poetry has a pull on us because it can mimic the rhythms of our lives.

We watched and produced performances. We loaded more than three hundred students onto buses and rode downtown to watch the Houston Grand Opera’s production of Romeo and Juliet. We considered what changes when actors are live, in front of us, as opposed to on a screen. Then we closed the year with our own performances of scenes from that play, and students had to consider how they could use their bodies as instruments to create the kind of meaning they imagined from the text.

I don’t consider my question fully answered, and I’m looking forward to continuing to work through it next year. I’ve been mulling over the motto that my own Latin teacher made us memorize: mens sana in corpore sano, or “a sound mind in a sound body.” If there is a relationship between physical and mental health, then surely there is a connection between the body and the brain when it comes to learning.

And I thought that was how I was going to end this post, but it’s not; I started writing this a month or so ago, which is to say prior to May 24, 2022. I have been thinking about bodies in classrooms all year long, but the events of that day – the massacre of elementary school children and their teachers – reified the issue for me. Those kids are never going to know how Shakespeare’s love sonnets echo their own heartbeats. They will never feel the way that their writing changes when they compose by holding a pen in hand and scratching on a sheet of paper as opposed to on a screen. They won’t experience learning bodily because their small, precious bodies have been destroyed.

I consider it as much my obligation to fight for the safety of bodies in classrooms as I do to consider the way that physicality impacts learning.